Bastyr University. B. Ur-Gosh, MD: "Buy Ashwagandha - Cheap Ashwagandha online OTC".

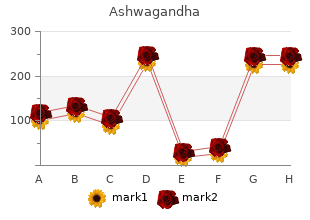

There are also groups of instruments that share similar names but perform different functions buy 60caps ashwagandha with amex anxiety side effects, e ashwagandha 60 caps visa anxiety zyprexa. Remember that the most important factor to consider when choosing an instrument is its function and purpose purchase ashwagandha 60 caps overnight delivery anxiety attacks symptoms. Quality is important, especially for instruments that you expect to use frequently and to last a long time. Buying the cheapest, low grade instruments can be a false economy, because they may need to be repaired or replaced more often. However, it may not be cost-effective to buy top grade instruments, because it will be expensive to replace them if they get lost. To help you judge the quality of instruments before you buy them, check that: • Edges of jaws and handles are even and smooth. Section 2 Procurement and management of supplies and equipment 33 • Surface is smooth, polished or stain finished. It is also useful to remember that: • Box joints are stronger and Shank Joint more stable than screw joints. Serrations may be 1×2 teeth crossways lengthways coarse or fine, run lengthways or crossways, run the whole way Parts of an instrument or only part way of the blade (see Appendix 3). Before first use, remove from their packaging, wash carefully, dry, lubricate moving parts, and store in a dry place. Hinged instruments, for example scissors, needle holders, and artery forceps, need regular lubrication. Only use water-based (or water- soluble) lubricants because these allow steam penetration during sterilisation, are anti-bacterial, inhibit corrosion, and prevent joints becoming stiff. For example, forceps should never be used as pliers or openers, surgical scissors should never be used for cutting gauze. This removes the protective layer and causes dirt and water to collect in the grooves, which results in corrosion, staining or rusting. Using the same solution several times reduces its effectiveness and increases the risk of corrosion, because of high concentrations of dirt and debris such as rust particles. The solution may become more concentrated because of evaporation, and this can also cause corrosion. For example, scissors should be closed to protect the cutting edge, and forceps closed on the first ratchet to prevent tension and stress. Do not use • If you have the choice, instruments should be sterilised cotton wool for drying. Refrigerators Your refrigerator provides a safe and reliable cold storage facility. The refrigerator should have two compartments: • Main compartment – kept at 0-8°C (or 2-8°C) – for vaccines and some drugs. Choosing a refrigerator • If your health facility has a stable and reliable supply of mains electricity choose a compression (electrical) refrigerator. The temperature in gas and electrical refrigerators is controlled by a thermostat. The temperature in a kerosene refrigerator is controlled manually by adjusting the kerosene burner wick up and down (a large flame makes the refrigerator colder and a small flame makes it warmer). Section 2 Procurement and management of supplies and equipment 35 General rules Following these simple rules will keep your refrigerator in good condition and ensure that it works efficiently. The room should be well-ventilated and the refrigerator kept away from sunlight, heat and draughts. Leave at least 20cm between the refrigerator, the wall and other equipment to allow hot air to escape from the back of the refrigerator. Make Ice packs sure that the refrigerator door seals perfectly, to prevent warm outside air Thermometer from entering. Check regularly storage cabinet all around the door seals for Water bottles damage and to make sure they seal properly. A simple way to do this is to place a sheet of paper between the door seal and cabinet and close the door. If the seal is working properly the paper Stocking the refrigerator stays in place and is not easy to pull out. Each time the door is opened, cold air escapes and warm air gets in, causing the temperature in the refrigerator to rise. Do not store food or drinks in the same refrigerator to avoid unnecessary opening of the door. If there is space, put containers of water in the bottom or the door of the refrigerator to keep contents cool when the door is opened. To check it is level, place a ball on top and adjust the refrigerator until the ball stops rolling. If possible place the refrigerator on a small timber pallet that keeps it off the ground by about 15cm. This stops water and moisture collecting under the refrigerator and so helps to prevent rusting. If air cannot circulate freely inside the refrigerator, the temperature will rise. Store vaccines in rows in trays, putting the same type of vaccines together in the same tray. The temperature pattern will show if there are any faults or the refrigerator is not working efficiently. If you have a kerosene refrigerator, refill the kerosene tank each day (record the amount of fuel added to the tank) and check the flame every morning and evening. Do not use knives or sharp instruments to remove ice as these can permanently damage the refrigerator. Do not use abrasives or bleach, because these will leave grooves that allow micro-organisms to multiply. But, only put stock back in the refrigerator when the required temperature (0-8°C) has been reached. People often make the mistake when a refrigerator has been defrosted of setting the thermostat at the coldest setting and restocking immediately with vaccines. Check that the door is sealing correctly and, if necessary, change the door gasket. Cleaning, disinfection and sterilisation are procedures used to prevent contamination and spread of infection by medical instruments and equipment. For reasons of safety, staff responsible for cleaning, disinfection and sterilisation should: • Wash their hands with soap and water. Practical tips for using water for cleaning, disinfection and sterilisation ● Use clean water (preferably filtered or boiled) for cleaning, disinfecting and sterilising. Water with a high mineral or salts content can damage equipment and instruments causing scaling, furring and corrosion of boilers and sterilisers. Boiling or filtering does not reduce the mineral or salts content of water but will ensure that the water is clean.

Leukemia 38 2 3 6 3 2 3 2 1 22 Other malignant neoplasms 99 3 2 2 5 13 20 16 10 71 B buy ashwagandha amex 8 tracks anxiety. Mental retardation cheap ashwagandha 60 caps online anxiety nausea, lead-caused 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Other neuropsychiatric disorders 46 1 2 1 1 1 1 11 6 23 F order ashwagandha with a mastercard anxiety 7 cups of tea. Hearing loss, adult onset — — — — — — — — — — Other sense organ disorders 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 G. Inflammatory heart diseases 71 2 1 2 4 6 7 8 4 34 Other cardiovascular diseases 372 4 4 9 12 26 32 41 27 154 H. Asthma 78 0 2 6 9 14 3 3 1 39 Other respiratory diseases 91 7 2 2 3 7 8 12 6 48 158 | Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors | Colin D. Appendicitis 7 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 4 Other digestive diseases 169 4 5 7 6 12 10 10 8 62 J. Benign prostatic hypertrophy 12 — — — 0 4 3 3 1 12 Other genitourinary system diseases 13 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 7 K. Low back pain 0 — — — — — 0 0 0 0 Other musculoskeletal disorders 8 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 4 M. Spina bifida 13 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 — 6 Other congenital anomalies 15 7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 N. War 26 0 0 10 8 3 1 0 0 23 Other intentional injuries 6 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 5 160 | Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors | Colin D. Note: — an estimate of zero; the number zero in a cell indicates a non-zero estimate of less than 500. Does not include liver cancer and cirrhosis deaths resulting from chronic hepatitis virus infection. This cause category includes “Causes arising in the perinatal period” as defined in the International Classification of Diseases, principally low birthweight, prematurity, birth asphyxia, and birth trauma, and does not include all causes of deaths occurring in the perinatal period. The Burden of Disease and Mortality by Condition: Data, Methods, and Results for 2001 | 161 Table 3B. Communicable, maternal, perinatal, 7,747 2,252 179 289 603 331 135 73 26 3,888 and nutritional conditions A. Hookworm disease 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Other intestinal infections 0 — 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Other infectious diseases 572 117 18 12 31 52 38 17 1 287 B. Birth asphyxia and birth trauma 240 139 — — — — — — — 139 Other perinatal conditions 90 52 — — — — — — — 52 E. Iron-deficiency anemia 18 5 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 8 Other nutritional disorders 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 162 | Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors | Colin D. Mental retardation, lead-caused 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 — — 0 Other neuropsychiatric disorders 32 5 3 2 2 2 2 1 0 18 F. Hearing loss, adult onset — — — — — — — — — — Other sense organ disorders 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 G. Inflammatory heart diseases 43 2 1 2 3 4 3 4 2 22 Other cardiovascular diseases 223 1 1 4 11 13 15 24 25 93 H. Asthma 26 1 0 1 2 3 3 3 1 13 Other respiratory diseases 112 8 1 4 7 12 12 12 6 62 164 | Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors | Colin D. Appendicitis 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Other digestive diseases 88 3 2 5 11 11 8 7 3 48 J. Benign prostatic hypertrophy 2 — — — — 0 0 1 1 2 Other genitourinary system diseases 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 2 K. Low back pain 0 — — — 0 0 0 0 — 0 Other musculoskeletal disorders 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 2 M. Spina bifida 4 2 0 0 — — — — — 2 Other congenital anomalies 31 15 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 17 N. War 136 0 1 53 43 16 7 2 1 123 Other intentional injuries 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 166 | Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors | Colin D. Note: — an estimate of zero; the number zero in a cell indicates a non-zero estimate of less than 500. Does not include liver cancer and cirrhosis deaths resulting from chronic hepatitis virus infection. This cause category includes “Causes arising in the perinatal period” as defined in the International Classification of Diseases, principally low birthweight, prematurity, birth asphyxia, and birth trauma, and does not include all causes of deaths occurring in the perinatal period. The Burden of Disease and Mortality by Condition: Data, Methods, and Results for 2001 | 167 Table 3B. Communicable, maternal, perinatal, 552 21 1 3 16 24 26 60 117 268 and nutritional conditions A. Hookworm disease 0 — 0 — 0 0 — 0 0 0 Other intestinal infections 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Other infectious diseases 84 1 0 1 2 5 6 11 13 39 B. Birth asphyxia and birth trauma 11 6 0 0 0 0 — — — 6 Other perinatal conditions 12 7 0 0 0 0 — — — 7 E. Iron-deficiency anemia 7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 Other nutritional disorders 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 168 | Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors | Colin D. Leukemia 73 0 1 2 2 5 8 13 9 41 Other malignant neoplasms 257 0 1 3 7 28 36 43 25 143 B. Mental retardation, lead-caused 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Other neuropsychiatric disorders 68 1 1 2 2 5 6 9 8 33 F. Hearing loss, adult onset — — — — — — — — — — Other sense organ disorders 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 G. Inflammatory heart diseases 72 0 0 1 3 7 8 11 10 41 Other cardiovascular diseases 676 1 0 2 8 21 34 74 139 279 H. Asthma 28 0 0 0 1 1 2 4 4 12 Other respiratory diseases 152 0 0 1 2 5 11 25 35 79 170 | Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors | Colin D. Appendicitis 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Other digestive diseases 189 1 0 1 4 11 13 24 30 83 J. Benign prostatic hypertrophy 2 — — 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 Other genitourinary system diseases 40 0 0 0 0 1 1 4 9 15 K. Low back pain 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Other musculoskeletal disorders 30 0 0 0 0 1 1 3 4 9 M. Spina bifida 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Other congenital anomalies 13 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 N. Violence 24 1 0 7 5 3 1 0 0 17 3 W ar Other intentional injuries 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 172 | Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors | Colin D. Note: — an estimate of zero; the number zero in a cell indicates a non-zero estimate of less than 500. Does not include liver cancer and cirrhosis deaths resulting from chronic hepatitis virus infection. This cause category includes “Causes arising in the perinatal period” as defined in the International Classification of Diseases, principally low birthweight, prematurity, birth asphyxia, and birth trauma, and does not include all causes of deaths occurring in the perinatal period. The Burden of Disease and Mortality by Condition: Data, Methods, and Results for 2001 | 173 Table 3B. Communicable, maternal, perinatal, 18,166 4,858 376 588 1,166 877 555 529 386 9,335 and nutritional conditions A.

Likewise effective 60 caps ashwagandha anxiety 38 weeks pregnant, including patients in the decision making process and responding to patient concerns with empathy encourages authentic communication and patient satisfaction (Barry & Edgman-Levitan best purchase for ashwagandha anxiety before period, 2012; Gelhaus order ashwagandha uk anxiety questionnaire, 2012a, 2012b; Platanova et al. Patients who do not feel heard, validated, or taken seriously by their doctors are likely to participate in self-advocacy behaviors (e. Research indicates that patients wish to work with their doctors—even patients who seek health information, refuse treatment, and self-treat (Barry & Edgman-Levitan, 2012; McNutt, 2010; Quaschning et al. However, traditionally, doctors have been taught to adopt a position of authority over their patients in order to ensure their patients’ recovery; and patients have been expected to accept a passive role and trust their doctors 244 (Lupton, 2003; Munch, 2004). According to MacDonald (2003), because society has changed and patients want to be active participants in their care, doctors must be willing to surrender some authority (p. As previously stated, I am not implying that doctors who work in a traditional relational-style deliberately intend to oppress their patients. Rather, because oppressive practices are systemically ingrained in society by historically- based knowledge and beliefs, “conscious and persistent effort [is required] to resist complicity in [the] patterns” of such practices (Sherwin, 1999, p. Historically oppressive practices in medicine continue to be challenged by patient-centered care initiatives in which doctor-patient collaboration is encouraged (Barry & Edgman-Levitan, 2012; Deber et al. As such, it is important for practicing doctors to work collaboratively with patients who prefer a collaborative relational style (Chin, 2002; Flynn et al. Furthermore, discussion of gender sensitive issues, sex differences in healthcare needs, and gender bias continues to be integrated into modern medical curriculum (Miller & Bahn, 2013; Pinn, 2013). As discussed previously, gender bias in medicine occurs as a result of stereotyped preconceptions about a person’s health, behavior, experiences, and needs based on their gender (Hamberg, 2008). From a feminist viewpoint, historically-based beliefs in psychology and biomedicine that women are fragile, unintelligent, and inferior to men continue to have a negative impact on both men and women (Chrisler, 2001; Hamberg, 2008; Hoffmann & Tarzian, 2001; Sherwin, 1999). In addition, “female disorders” in psychology and biomedicine—or disorders that are typically assigned to women based on stereotypes—are often unrecognized and misdiagnosed in men (Boysena, Ebersolea, Casnera, & Coston, 2014; Field et al. For example, men are undertreated for osteoporosis and eating disorders as compared to women because these disorders are traditionally thought of as “feminine” (Field et al. Likewise, women are undertreated for back and chest pain as compared to men because these symptoms tend to be thought of as “masculine” (Chang et al. Thus, it is essential that doctors recognize the potential for gender bias and to remain current with the literature regarding the illnesses they treat (Napoli et al. In conjunction with feminism, a social constructionist perspective of illness asserts that objective views of the human body are socially constructed (Fernandes et al. From a feminist/social constructionist viewpoint, patients’ interpretations of their own illness experiences are valid and patients are considered experts of their own medical conditions (Chrisler, 2001; Docherty & McColl, 2003; Hoffmann & Tarzian, 2001; Lupton, 2003). Adopting a feminist/social constructionist approach to medicine encourages patients and doctors to question concepts of “normal” and “healthy” and for doctors to consider 246 patients’ subjective interpretations of their own illness—techniques that are characteristic of patient-centered care (Barry & Edgman-Levitan, 2012; Hoffmann & Tarzian, 2001; Levinson et al. The reported experiences of the women in the current study provide information with which one might begin to understand the treatment experiences of women with thyroid disease and their relationships with their doctors. Overall, the most commonly expressed needs shared by participants were to feel heard and be taken seriously by their doctors—both of which are common in collaborative doctor-patient relationships and patient-centered practices. Doctors who diagnose and treat women with thyroid disease are in a position to empower their patients. Based on the results of the current study, women who have thyroid disease desperately wish to feel well again and for their experiences to be known and understood. Further research on the treatment experiences of women with thyroid disease and the doctor-patient relationship is imperative for better understanding the unique needs of female thyroid patients in order to more accurately diagnose and effectively treat this debilitating and potentially life-threatening disease. How missing information in diagnosis can lead to disparities in the clinical encounter. Commentary: “Increasing minority participation in clinical research”: A white paper from the Endocrine Society. Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Relation of diabetic patients’ health-related control appraisals and physician–patient interpersonal impacts to patients’ metabolic control and satisfaction with treatment. Patients, providers, and systems need to acquire a specific set of competencies to achieve truly patient-centered care. On the contextual nature of sex-related biases in pain judgments: The effects of pain duration, patient’s distress and judge’s sex. Patient-centered care: The influence of patient and resident physician gender and gender concordance in primary care. Medical students’ gender is a predictor of success in the obstetrics and gynecology basic clerkship. Sex differences and/in the self: Classic themes, feminist variations, postmodern challenges. Holistic solutions for anxiety & depression in therapy: Combining natural remedies with conventional care. Cognitive and affective status in mild hypothyroidism and interactions with l-thyroxine treatment. Gendered mental disorders: Masculine and feminine stereotypes about mental disorders and their relation to stigma. Improving doctor-patient communication: Examining innovative modalities vis-à-vis effective patient-centric care management technology. Shared-decision making in general practice: Do patients with respiratory tract infections actually want it? Congruence between patients’ preferred and perceived participation in medical decision making: A review of the literature. Psychiatric manifestations of Graves’ hyperthyroidism: Pathophysiology and treatment options. Patients’ views on changes in doctor-patient communication between 1982 and 2001: A mixed- methods study. Information seeking and satisfaction with physician- patient communication among prostate cancer survivors. Gender bias in cardiovascular testing persists after adjustment for presenting characteristics and cardiac risk. Considering ‘‘the professional’’ in communication studies: Implications for theory and research within and beyond the boundaries of organizational communication. Undergraduate students’ attitudes to communication skills learning differ depending on year of study and gender. Relationship between communication skills training and doctors’ perceptions of patient similarity. A spatial analysis of variations in health access: Linking geography, socio-economic status and access perceptions. Patient satisfaction: African American women’s views of the patient-doctor relationship. Characteristics of online and offline health information seekers and factors that discriminate between them. A 3-stage model of patient-centered communication for addressing cancer patients’ emotional distress. The role of expectations in preferences of patients for a female or male general practitioner. The influence of attitudes toward male and female patients on treatment decisions in general practice.

Strengths A wide range of tools applied across a diverse range of channels and settings were identified in the review purchase 60caps ashwagandha with mastercard anxiety 8dpo. Weaknesses • Most interventions relied exclusively on communication tools to put theories and models into practice discount ashwagandha 60 caps without a prescription anxiety in teens. Strengths • The review included sixty-one evaluations of interventions for the prevention/control of communicable disease that used a theory or model of behaviour change [282-343] discount 60 caps ashwagandha fast delivery anxiety 60 mg cymbalta 90 mg prozac. Quality Twenty-one of the sixty-one studies included in the review were rated as of high quality (i. Weaknesses There is a lack of evidence on the cost-effectiveness of theory-based interventions, with only one study included in the review reporting on implementation costs [286]. Quality Six of the nine European studies included in the review were rated below the threshold for high quality [286, 292, 301, 327, 330, 337]. Only three of the nine European studies were rated as of high quality [282, 302, 331]. Weaknesses Communication effects Included studies did not report sufficient detail on communication-based indicators of change to draw any inferences or conclusions on outcomes. Behavioural and other changes The studies included in the review highlight a need for more research on the nature and strength of association between behaviour and behavioural determinants. Many of the included individual-level and interpersonal-level theory based interventions targeted common intermediate variables but did not measure change. This represents a lost opportunity to pool evidence through meta-analysis or other methods to identify and measure treatment for, or effects size of, modifiable factors shared by the various theories and models (e. Application What has been applied into practice regarding the use of theories and models of behaviour change? European Fifteen per cent (n=9) of intervention studies captured by the review were from European settings [282, 286, 292, 301-302, 327, 330-331, 337]. Targeting including hard-to-reach populations • A wide range of target audiences, in particular a large body of evidence reporting on health professionals (n= 16) [282, 285-286, 289-290, 299-300, 302, 308, 312, 314, 317-318, 324, 337-340]. Weaknesses European There is an imbalance with relatively less evidence for lay persons (e. The reference numbering system used in this table does not stem from the completed review, published in the technical report series as: Angus K, Cairns G, Purves R, Bryce S, MacDonald L, Gordon R. Systematic literature review to examine the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions that use theories and models of behaviour change: towards the prevention and control of communicable diseases. The synthesis of evidence [1-9] highlights the most significant strengths and gaps in the European evidence base currently available for health communication in the prevention and control of communicable diseases. While there were many strengths and weaknesses evident, overall, it is apparent that there is a limited evidence base focusing on prevention and control of communicable diseases in a European context. Much of the evidence originated from North America and draws substantially on evidence from non-communicable diseases and other health issues. Therefore, the transferability of this knowledge, learning, expertise, and best practice should be explored in order to develop capacity. However, it is also evident that there is a lack of knowledge on how to use health communications to effectively engage and improve health outcomes for hard-to-reach groups [1-9], even though they carry the most significant burden of disease, have the poorest access to services and are found to be disproportionally affected during communicable disease outbreaks [7]. The reviews also indicated that within the current evidence base, there was: methodological variability, a lack of rigorous evaluation, inconsistent reporting, and lack of empirical studies and use of standardised measures, heterogeneity of interventions and evaluations. These limitations highlight the need for enhanced development and support of health communication research capacity in Europe. This is required in order to facilitate the development of a high-quality robust evidence base. Overall, while there is a limited European evidence base for health communication and communicable diseases, there is also evidence indicating some, albeit limited capacity across Europe. The implications of these findings, their relevance and suggested action areas for the future development of capacity for effective communication for the prevention and control of communicable diseases are discussed further in Chapter 3 of this report. Evidence review: social marketing for the prevention and control of communicable disease. A literature review on health information-seeking behaviour on the web: a health consumer and health professional perspective. A literature review of trust and reputation management in communicable disease public health. Health communication campaign evaluation with regard to the prevention and control of communicable diseases in Europe. A literature review on effective risk communication for the prevention and control of communicable diseases in Europe. Systematic literature review of the evidence for effective national immunisation schedule promotional communications. Systematic literature review to examine the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions that use theories and models of behaviour change: towards the prevention and control of communicable diseases. Barry Chapter 2 Opportunities and challenges: The consultation phases Introduction This chapter presents the evidence from the consultation phases of the Translating Health Communication Project. The matrices in this chapter, focusing on the identification of opportunities and challenges through primary data collection, complement those presented in Chapter 1, where the focus was on strengths and weaknesses of the evidence. The consultation comprised an e-survey and telephone interviews, and full information about the methodology used can be accessed in Doyle et al. The data from the e-survey was collected between October and December 2010, and 65 participants completed the survey. The semi-structured telephone interviews were designed to obtain more in-depth information on health communication activities. These were undertaken between October 2010 and March 2011, and 44 key informants participated. Using questions drawn from the findings of the e-survey, an expert consultation was conducted in Budapest, Hungary, on 21 March 2011. The protocol comprised of nine questions and covered domains such as health communication: examples, gaps, barriers, priorities, capacity and needs with regard to communicable diseases. The complete results of this consultation are presented in Doyle, Sixsmith and Barry, 2011 [2]. Data was gathered using asynchronous communication via a private electronic mailing list and supported by an interactive website/e-forum which provided access to project information and relevant resources, including 3 Participants identified what they would like to happen in the future for health communication. These participants had a wide range of public health and health communication expertise and were employed by a diversity of organisations. Primary information gathering Challenges and opportunities identified The first matrix presented in Table 2. The subsequent matrices in this chapter present the data collected through the e-forum [3]. Please note that for the twelve participants that took part in the online email consultation, personal identifiers were removed and replaced with participant numbers, thus any direct quotes from these participants will be labelled as such, for example ‘P1’. Opportunities To enhance collaborative working and strengthen partnerships and professional networks among those working in the area of health communication and communicable disease within countries and across all Member States. Opportunities • An opportunity exists to facilitate development of guidelines and tools to support health communication in a consistent way, for example developing health communication strategies and plans.

Purchase ashwagandha 60caps fast delivery. Live Sound Bath for Reducing Stress & Anxiety | Gong Healing Meditation | Vibrational Music Therapy.