Iowa Wesleyan College. T. Nafalem, MD: "Order Provigil online no RX - Proven Provigil no RX".

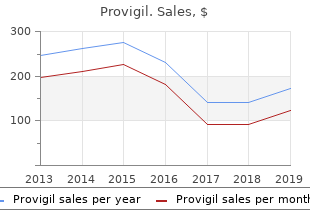

However buy 100mg provigil otc insomnia game, obesity treatment using dieting is an example of the potential negative side effects of encouraging individual responsibility for health and attempting to change behaviour buy 100 mg provigil otc insomnia treatment guidelines. Perhaps behavioural interventions can have as many negative consequences as other medical treatments order generic provigil on-line insomnia synonym. Theories are considered either physio- logical or psychological and treatment perspectives are divided in a similar fashion, therefore maintaining a dualistic model of individuals. This paper discusses the recent emphasis on patient responsibility for health and suggests that encouraging the obese to diet may be an example of attempting to control the uncontrollable. This book provides an account of the continuum of eating behaviour from healthy eating, through dieting and body dissatisfaction, obesity and eating disorders. In addition, it describes the ways in which quality of life has been used in research both in terms of the factors that predict quality of life (quality of life as an outcome variable) and the association between quality of life and longevity (quality of life as a predictor). The question asked is, ‘Has the number of people who have died this year gone up, gone down or stayed the same? The next most basic form of mortality rate therefore includes a denominator reflecting the size of the population being studied. Such a measure allows for com- parisons to be made between different populations: more people may die in a given year in London when compared with Bournemouth, but London is simply bigger. In order to provide any meaningful measure of health status, mortality rates are corrected for age (Bournemouth has an older population and therefore we would predict that more people would die each year) and sex (men generally die younger than women and this needs to be taken into account). Furthermore, mortality rates can be produced to be either age specific such as infant mortality rates, or illness specific such as sudden death rates. As long as the population being studied is accurately specified, corrected and specific, mortality rates provide an easily available and simple measure: death is a good reliable outcome. However, the juxtaposition of social scientists to the medical world has challenged this position to raise the now seemingly obvious question, ‘Is health really only the absence of death? However, in line with the emphasis upon simplicity inherent within the focus on mortality rates, many morbidity measures still use methods of counting and recording. For example, the expensive and time-consuming production of morbidity prevalence rates involve large surveys of ‘caseness’ to simply count how many people within a given population suffer from a particular problem. Likewise, sick- ness absence rates simply count days lost due to illness and caseload assessments count the number of people who visit their general practitioner or hospital within a given time frame. However, morbidity is also measured for each individual using measures of functioning. Some of these are referred to simply as subjective health measures, others are referred to as either quality of life scales or health-related quality of life scales. However, the literature in the area of subjective health status and quality of life is plagued by two main questions: ‘What is quality of life? Reports of a Medline search on the term ‘quality of life’ indicate a surge in its use from 40 citations (1966–74), to 1907 citations (1981–85), to 5078 citations (1986–90) (Albrecht 1994). For example, it has been defined as ‘the value assigned to duration of life as modified by the impairments, functional states, perceptions and social opportunities that are influenced by disease, injury, treatment or policy’ (Patrick and Ericson 1993), ‘a personal statement of the positivity or negativity of attributes that characterise one’s life’ (Grant et al. Further, whilst some researchers treat the concepts of quality of life as interchangeable, others argue that they are separate (Bradley 2001). Such problems with definition have resulted in a range of ways of operationalizing quality of life. For example, following the discussions about an acceptable definition of quality of life, the European Organisation for Research on Treatment of Cancer operationalized quality of life in terms of ‘functional status, cancer and treatment specific symptoms, psychological distress, social interaction, financial/economic impact, perceived health status and overall quality of life’ (Aaronson et al. In line with this, their measure consisted of items that reflected these different dimensions. Furthermore, Fallowfield (1990) defined the four main dimensions of quality of life as psychological (mood, emotional distress, adjustment to illness), social (relationships, social and leisure activities), occupational (paid and unpaid work) and physical (mobility, pain, sleep and appetite). Creating a conceptual framework In response to the problems of defining quality of life, researchers have recently attempted to create a clearer conceptual framework for this construct. In particular, researchers have divided quality of life measures either according to who devises the measure or in terms of whether the measure is considered objective or subjective. The first of these is described as being based on the assumption that ‘a consensus about what constitutes a good or poor quality of life exists or at least can be discovered through investigation’ (Browne et al. In addition, the standard needs approach assumes that needs rather than wants are central to quality of life and that these needs are common to all, including the researchers. In contrast, the psychological processes approach considers quality of life to be ‘constructed from individual evaluations of personally salient aspects of life’ (Browne et al. They argued that quality of life measures should be divided into those that assess objective functioning and those that assess subjective well-being. The first of these reflects those measures that describe an individual’s level of functioning, which they argue must be validated against directly observed behavioural performance, and the second describes the individual’s own appraisal of their well-being. Therefore, some progress has been made to clarify the problems surrounding measures of quality of life. However, until a consensus among researchers and clinicians exists it remains unclear what quality of life is, and whether quality of life is different to subjective health status and health-related quality of life. However, ‘quality of life’, ‘subjective health status’ and ‘health-related quality of life’ continue to be used and their measurement continues to be taken. The range of measures developed will now be considered in terms of (1) unidimensional measures and (2) multidimensional measures. Whilst the short form is mainly used to explore mood in general and provides results as to an individual’s relative mood (i. Therefore, these unidimensional measures assess health in terms of one specific aspect of health and can be used on their own or in conjunction with other measures. Multidimensional measures Multidimensional measures assess health in the broadest sense. For example, researchers often use a single item such as, ‘would you say your health is: excellent/good/fair/poor? Further, some researchers simply ask respondents to make a relative judgement about their health on a scale from ‘best possible’ to ‘worst possible’. Although these simple measures do not provide as much detail as longer measures, they have been shown to correlate highly with other more complex measures and to be useful as an outcome measure (Idler and Kasl 1995). Because of the many ways of defining quality of life, many different measures have been developed. Some focus on particular populations, such as the elderly (Lawton 1972, 1975; McKee et al. In addition, generic measures of quality of life have also been developed, which can be applied to all individuals. All of these measures have been criticized for being too broad and therefore resulting in a definition of quality of life that is all encompassing, vague and unfocused. In particular, it has been suggested that by asking individuals to answer a pre-defined set of questions and to rate statements that have been developed by researchers, the indi- vidual’s own concerns may be missed. Individual quality of life measures Measures of subjective health status ask the individual to rate their own health. This is in great contrast to measures of mortality, morbidity and most measures of functioning, which are completed by carers, researchers or an observer. However, although such measures enable individuals to rate their own health, they do not allow them to select the dimensions along which to rate it. For example, a measure that asks about an individual’s work life assumes that work is important to this person, but they might not want to work.

Diseases

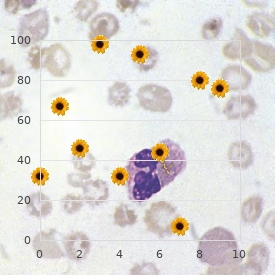

Protozoa are microorganisms in various sizes and forms that may be free-living or parasitic generic provigil 100mg free shipping sleep aid ear muffs. They possess a nucleus containing chromo- somes and organelles such as mitochondria (lacking in some cases) buy cheap provigil line sleep aid doxylamine succinate side effects, an en- Kayser cheap 200 mg provigil overnight delivery sleep aid lavender oil, Medical Microbiology © 2005 Thieme All rights reserved. Host–Pathogen Interactions 7 doplasmic reticulum, pseudopods, flagella, cilia, kinetoplasts, etc. Many para- sitic protozoa are transmitted by arthropods, whereby multiplication and 1 transformation into the infectious stage take place in the vector. Medically signif- icant groups include the trematodes (flukes or flatworms), cestodes (tape- worms), and nematodes (roundworms). These animals are characterized by an external chitin skele- ton, segmented bodies, jointed legs, special mouthparts, and other specific features. Their role as direct causative agents of diseases is a minor one (mites, for instance, cause scabies) as compared to their role as vectors trans- mitting viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and helminths. Host–Pathogen Interactions & The factors determining the genesis, clinical picture and outcome of an infection include complex relationships between the host and invading or- ganisms that differ widely depending on the pathogen involved. Despite this variability, a number of general principles apply to the interactions be- tween the invading pathogen with its aggression factors and the host with its defenses. Since the pathogenesis of bacterial infectious diseases has been re- searched very thoroughly, the following summary is based on the host–in- vader interactions seen in this type of infection. The determinants of bacterial pathogenicity and virulence can be outlined as follows: & Adhesion to host cells (adhesins). The above bacterial pathogenicity factors are confronted by the following host defense mechanisms: & Nonspecific defenses including mechanical, humoral, and cellular sys- tems. The response of these defenses to infection thus involves the correlation of a number of different mechanisms. Primary, innate defects are rare, whereas acquired, sec- ondary immune defects occur frequently, paving the way for infections by microorganisms known as “facultative pathogens” (opportunists). The terms pathogenicity and virulence are not clearly defined in their relevance to microorganisms. It has been proposed that pathogenicity be used to characterize a particular species and that virulence be used to describe the sum of the disease-causing properties of a population (strain) of a pathogenic species (Fig. Determinants of Bacterial Pathogenicity and Virulence Relatively little is known about the factors determining the pathogenicity and virulence of microorganisms, and most of what we do know concerns the disease-causing mechanisms of bacteria. Host–Pathogen Interactions 11 Virulence, Pathogenicity, Susceptibility, Disposition 1 virulent strain avirulent type or var (e. The terms disposi- tion and resistance are used to characterize the status of individuals of a suscep- tible host species. There are five groups of potential bacterial contributors to the pathogen- esis of infectious diseases: 1. Adhesion When pathogenic bacteria come into contact with intact human surface tis- sues (e. This is a specific process, meaning that the adhesion structure (or ligand) and the receptor must fit together like a key in a keyhole. Bacteria may invade a host passively through microtraumata or macrotraumata in the skin or mucosa. On the other hand, bacteria that invade through intact mucosa first adhere to this anatomical barrier, then actively breach it. Different bacterial species deploy a variety of mechanisms to reach this end: — Production of tissue-damaging exoenzymes that destroy anatomical bar- riers. Bacteria translocated into the intracellular space by endocytosis cause actin to condense into filaments, which then array at one end of the bacterium and push up against the inner side of the cell membrane. This is followed by fusion with the membrane of the neighboring tissue cell, whereupon the bacterium enters the new cell (typical of Listeria and Shigella). Strategies against Nonspecific Immunity Establishment of a bacterial infection in a host presupposes the capacity of the invaders to overcome the host’s nonspecific immune defenses. The most important mechanisms used by pathogenic bacteria are: Kayser, Medical Microbiology © 2005 Thieme All rights reserved. Capsule components may 1 block alternative activation of complement so that C3b is lacking (ligand for C3b receptor of phagocytes) on the surface of encapsulated bacteria. Microorganisms that use this strategy include Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae. A lipopolysaccharide in the outer membrane is modified in such a way that it cannot initiate alternative activation of the complement system. As a result, the membrane attack complex (C5b6789), which would otherwise lyse holes in the outer membrane, is no longer produced (see p. They complex with iron, thereby stealing this element from proteins containing iron (transferrin, lactoferrin). The intricate iron transport system is localized in the cytoplasmic membrane, and in Gram- negative bacteria in the outer membrane as well. The free availability of only about 10–20 mol/l iron in human body fluids thus presents a challenge to them. At this stage of development, the immune system is un- able to recognize bacterial immunogens as foreign. Molecular mimicry refers to the presence of molecules on the surface of bacteria that are not recognized as foreign by the im- mune system. Examples of this strategy are the hyaluronic acid capsule of Streptococcus pyogenes or the neuraminic acid capsule of Escherichia coli K1 and serotype B Neisseria meningitidis. Mucosal immunity to gonococci depends on antibodies in the secretions of the urogenital mucosa that attach to the immunodominant seg- ment of the pilin, thus blocking adhesion of gonococci to the target cells. The gonococcal genome has many other pil genes besides the pilE without promoters, i. Intracellular homologous recombination of conserved regions of silent pil genes and corre- sponding sequences of the expressed gene results in pilE genes with changed cas- settes. Some bacteria are characterized by a pronounced variability of their immunogens (= immune antigens) due to the genetic variability of the structural genes coding the antigen proteins. This results in production of a series of antigen variants in the course of an infection that no longer “match” with the antibodies to the “old” antigen. Examples: gonococci can modify the primary structure of the pilin of their attachment Kayser, Medical Microbiology © 2005 Thieme All rights reserved. The borreliae that cause relapsing fevers have the capacity to change the structure of one of the adhesion proteins in their outer 1 membrane (vmp = variable major protein), resulting in the typical “recur- rences” of fever. Similarly, meningococci can change the chemistry of their capsule polysaccharides (“capsule switching”). Mucosal secretions contain the secretory antibodies of the sIgA1 class responsible for the specific local immunity of the mucosa. Classic mucosal parasites such as gonococci, meningococci and Haemophilus influ- enzae produce proteases that destroy this immunoglobulin. Clinical Disease The clinical symptoms of a bacterial infection arise from the effects of dama- ging noxae produced by the bacteria as well as from excessive host immune responses, both nonspecific and specific. Immune reactions can thus poten- tially damage the host’s health as well as protect it (see Immunology, p.

Diseases

His immunosuppression needs to continue and should be kept at as low a dose as is compatible with preventing rejection of his transplant order provigil discount insomnia with zoloft. The diagnosis of the lesion was made by biopsy purchase line provigil insomnia 46, which showed a squamous cell cancer purchase provigil in india sleep aid target. An essential part of the follow-up is regular review, at least 6-monthly, of the skin to detect any recurrence, any new lesions or malig- nant transformation of the solar hyperkeratoses. Her appetite is normal, she has no nausea or vomiting and she has not lost weight. Physical examination at this time was completely normal, with a blood pres- sure of 128/72 mmHg. Investigations showed normal full blood count, urea, creatinine and electrolytes, and liver function tests. An H2 antagonist was prescribed and follow-up advised if her symptoms did not resolve. There was slight relief at first, but after 1 month the pain became more frequent and severe, and the patient noticed that it was relieved by sitting forward. Despite the progressive symptoms she and her husband went on a 2-week holiday to Scandinavia which had been booked long before. During the second week her husband remarked that her eyes had become slightly yellow, and a few days later she noticed that her urine had become dark and her stools pale. Examination She was found to have yellow sclerae with a slight yellow tinge to the skin. The pain has two typical features of carcinoma of the pancreas: relief by sitting forward and radiation to the back. As with obstruction of any part of the body the objective is to define the site of obstruc- tion and its cause. The initial investigation was an abdominal ultrasound which showed a dilated intrahepatic biliary tree, common bile duct and gallbladder but no gallstones. The pancreas appeared normal, but it is not always sensitive to this examination owing to its depth within the body. It showed a small tumour in the head of the pancreas causing obstruction to the common bile duct, but no extension outside the pancreas. The patient underwent partial pancreatectomy with anastamosis of the pancreatic duct to the duodenum. Follow-up is necessary not only to detect any recurrence but also to treat any possible development of diabetes. During the singing of a hymn she suddenly fell to the ground without any loss of consciousness and told the other members of the congregation who rushed to her aid that she had a complete par- alysis of her left leg. She has no relevant past or family history, is on no medication and has never smoked or drunk alcohol. She works as a sales assistant in a bookshop and until recently lived in a flat with a partner of 3 years’ standing until they split up 4 weeks previously. Examination She looks well, and is in no distress; making light of her condition with the staff. The left leg is completely still during the examination, and the patient is unable to move it on request. Superficial sensation was completely absent below the margin of the left buttock and the left groin, with a clear transition to normal above this circumference at the top of the left leg. There was normal withdrawal of the leg to nociceptive stimuli such as firm stroking of the sole and increasing compression of Achilles’ tendon. The superficial reflexes and tendon reflexes were normal and the plantar response was flexor. The clues to this are the cluster of: • the bizarre complex of neurological symptoms and signs which do not fit neuroanatom- ical principles, e. None of these on its own is specific for the diagnosis but put together they are typical. In any case of dissociative disorder the diagnosis is one of exclusion; in this case the neuro- logical examination excludes organic lesions. It is important to realize that this disorder is distinct from malingering and factitious disease. The condition is real to patients and they must not be told that they are faking illness or wasting the time of staff. The management is to explain the dissociation – in this case it is between her will to move her leg and its failure to respond – as being due to stress, and that there is no underlying serious disease such as multiple sclerosis. A very positive attitude that she will recover is essential, and it is important to reinforce this with appropriate physical treatment, in this case physiotherapy. The prognosis in cases of recent onset is good, and this patient made a complete recovery in 8 days. Dissociative disorder frequently presents with neurological symptoms, and the commonest of these are convulsions, blindness, pain and amnesia. Clearly some of these will require full neurological investigation to exclude organic disease. She lives alone but one of her daughters, a retired nurse, moves in to look after her. The patient has a long history of rheumatoid arthritis which is still active and for which she has taken 7 mg of prednisolone daily for 9 years. For 5 days since 2 days before starting the antibiotics she has been feverish, anorexic and confined to bed. On the fifth day she became drowsy and her daughter had increasing difficulty in rousing her, so she called an ambulance to take her to the emergency department. Examination She is small (assessed as 50 kg) but there is no evidence of recent weight loss. Her pulse is 118/min, blood pressure 104/68 mmHg and the jugular venous pressure is not raised. Her joints show slight active inflammation and deformity, in keeping with the history of rheumatoid arthritis. This is a common problem in patients on long-term steroids and arises when there is a need for increased glucocorticoid output, most frequently seen in infections or trauma, including surgery, or when the patient has prolonged vomiting and therefore cannot take the oral steroid effect- ively. It is probably due to a combination of reduced intake of sodium owing to the anorexia, and dilution of plasma by the fluid intake. In secondary hypoaldosteronism the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system is intact and should operate to retain sodium. This is in contrast to acute primary hypoaldosternism (Addisonian crisis) when the mineralocorticoid secretion fails as well as the glucocorticoid secretion, causing hyponatraemia and hyperkalaemia. Acute secondary hypoaldosteronism is often but erroneously called an Addisonian crisis. Spread of the infection should also be considered, the prime sites being to the brain, with either meningitis or cerebral abscess, or locally to cause a pulmonary abscess or empyema. The patient has a degree of immunosuppression due to her age and the long-term steroid. The dose of steroid is higher than may appear at first sight as the patient is only 50 kg; drug doses are usually quoted for a 70 kg male, which in this case would equate to 10 mg of prednisolone, i. The treatment is immediate empirical intravenous infusion of hydrocortisone and saline.