DeVry University, Columbus. K. Luca, MD: "Order Shallaki online no RX - Effective online Shallaki".

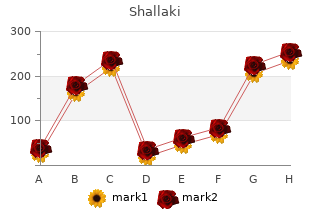

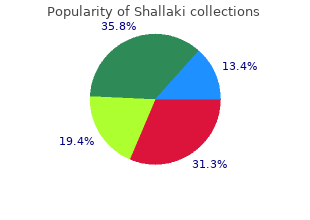

They receive lymph from the external and internal iliac nodes and send it to the lateral aortic nodes buy shallaki master card spasms quadriceps. They receive most of the lymph of the pelvic organs and from the deeper tissues of the perineum 60caps shallaki fast delivery spasms of the colon. They also receive some vessels of the lower limbs that travel along the superior and inferior gluteal blood vessels discount shallaki 60 caps amex spasms in your stomach. They also receive direct lymph vessels from the deeper tissues of the infraumbilical part of the anterior abdominal wall and from some pelvic organs. Draw another vertical line separating the pyloric part of the stomach (Area D) from the body. Divide the area between these two vertical lines into two unequal parts by a curved line drawn parallel to the greater curvature so that the area above it (Area B) is larger (2/3rd) than the area (c) below it. Area A drains into the pancreaticosplenic nodes lying along the splenic artery (i. Lymph vessels from these nodes travel along the splenic artery to reach the coeliac nodes. Area B drains into the left gastric nodes lying along the artery of the same name. Area c drains into the right gastroepiploic nodes that lie along the artery of the same name. Lymph vessels arising in these nodes drain into the pyloric nodes that lie in the angle between the frst and second parts Chapter 34 ¦ Lym phatics and Autonom ic Nerves of Abdom en and Pelvis 687 of the duodenum. From here the lymph is drained further into the hepatic nodes that lie along the hepatic artery; and fnally into coeliac nodes. Lymph from area D drains in different directions into the pyloric, hepatic and left gastric nodes, and passes from all these nodes to the coeliac nodes. Note that lymph from all areas of the stomach ultimately reaches the coeliac nodes. From here it passes through the intestinal lymph trunk to reach the cisterna chyli. Most of the lymph vessels from the duodenum end in the pancreaticoduodenal nodes present along the inside of the curve of the duodenum (i. From here the lymph passes partly to the hepatic nodes, and through them to the coeliac nodes and partly to the superior mesenteric nodes. Some vessels from the frst part of the duodenum drain into the pyloric nodes, and through them to the hepatic nodes. Lymph from lacteals drains into plexuses in the wall of the gut and from there to vessels in the mesentery (34. It ultimately reaches lymph nodes present in front of the aorta at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery. Before reaching these nodes the lymph from the intestines passes through hundreds of lymph nodes located in the mesentery. The terminal part of the ileum is drained, in a similar manner, by nodes lying along the ileocolic artery and its ileal branch (see 34. The lymph from the caecum and appendix drains into the superior mesenteric lymph nodes after passing through the several outlying nodes. The outlying nodes are present along the ileocolic artery and its anterior caecal, posterior caecal and appendic- ular branches (anterior ileocolic nodes; posterior ileocolic nodes and appendicular nodes respectively)(34. The ascending colon and the transverse colon drain into the superior mesenteric group of preaortic nodes. The descending colon and sigmoid colon drain into the inferior mesenteric group of preaortic nodes. Along the right and middle colic branches of the superior mesenteric artery and the left colic branch of the inferior mesenteric artery. The upper part of the rectum drains to the inferior mesenteric nodes through vessels passing along the inferior mesenteric artery (‘1’ in 34. The lower part of the rectum and the upper part of the anal canal drain into the internal iliac nodes through vessels running along the middle rectal artery. Part of the liver near the inferior vena cava (including parts of the posterior, superior and inferior surfaces) drains to nodes around the upper end of the inferior vena cava (‘a’ in 34. Most of the inferior surface and the adjoining part of the anterior surface drain to nodes in the porta hepatis (‘b’ in 34. Part of the convex anterosuperior surface drains directly to the coeliac nodes (‘c’ in 34. Some vessels ascend along the hepatic veins and end in nodes around the upper end of the inferior vena cava (‘d’ in 34. The gall bladder and bile duct drain to the hepatic nodes (lying along the hepatic artery), and through them to the coeliac nodes (34. Vessels from the lower end of the bile duct drain into the pancreaticoduodenal nodes. The pancreaticoduodenal nodes lying at the junction of pancreas and duodenum (both anteriorly and pos- teriorly) (34. From these nodes most of the lymph drain into the coeliac nodes, but some of it drain into the superior mesenteric nodes. Lym phatic Drainage of Kidney All lymph vessels from the kidneys drain directly into the lateral aortic nodes. The upper abdominal part of the ureter drains directly to the lateral aortic nodes. The pelvic part of the ureter drains into the external iliac and internal iliac nodes. Lym phatic Drainage of Urinary Bladder the urinary bladder drains into the external iliac lymph nodes. The prostatic and membranous parts of the urethra drain into the internal iliac lymph nodes. Lym phatic Drainage of Testes and Ovaries Lymph from the testis or ovary passes along the testicular or ovarian vessels directly to the lateral aortic lymph nodes. Superfcial structures in the perineum including the lower part of the anal canal (34. The skin above the level of the umbilicus (in front) and above the iliac crest (at the back) drains into the axillary lymph nodes. The skin of the anterior abdominal wall below the umbilicus drains into the superfcial inguinal lymph nodes. Lymph vessels from the posterior abdominal wall travel along the lumbar vessels to the lateral aortic nodes, including the retroaortic nodes. The vessels from the upper part of the anterior and lateral part of the abdominal wall travel along the superior epigastric vessels to the parasternal nodes. The vessels from the lower part of the anterolateral abdominal wall travel along the inferior epigastric and circumfex iliac vessels. Passing through nodes placed along these vessels they reach the external iliac nodes. Sympathetic nerves to be seen in the abdomen and pelvis are branches given off by the sympathetic trunk in this region. Some branches given off by the thoracic part of the sympathetic trunk also enter the abdomen.

However buy shallaki canada muscle relaxant walgreens, it can be argued that with a clinician’s ethical principles or with a clinical decision support systems may have a use- patient’s preferences for treatment (Patel et al ful role in education (Gozum 1994) best shallaki 60 caps muscle relaxant anticholinergic. Moreover order 60 caps shallaki otc spasms near gall bladder, the analyses based on Bayesian students a degree of practice in solving simulated rules require comprehensive knowledge of all the but realistic cases in a safe environment where available alternatives and their consequences, and patients will not be harmed. Bradley the 1990s saw the beginning of exploration into (1993) noted that designing decision trees requires the process by which dental clinical decisions are a certain degree of artistry and expertise. This is not made, largely under the influence of the theory of a mechanical or automatic process. The hypothetico-deduc- some interpretive creativity is required when con- tive (H-D) model (Elstein et al 1978) serves as the structing decision trees. It can be argued that basis for problem-based learning in dentistry and decision theory implicitly relies upon such inter- in medicine. It identifies four stages in solving pretive creativity, even though the conceptual problems: cue acquisition, generation of hypothe- framework and vocabulary of decision theory have sis, cue interpretation and evaluation of hypo- no place for artistry. A more elaborate model of H-D reasoning support for further development of decision sup- addresses the actual thinking process used when port systems based on Bayesian rules. However, H-D mod- 1980s with a range of computer-based decision els cannot adequately explain the diagnostic support systems for diagnosis and treatment reasoning of dental students when confronted by planning in several dental specialties, such as a typically routine dental problem, such as manag- orthodontics (Sims-Williams et al 1987), prostho- ing a patient with caries. Apparently, students dontics (Kawahata & MacEntee 2002) and oral combine various strategies of H-D reasoning with medicine (Hubar et al 1990). Initially the systems aspects of pattern recognition to make diagnostic were simplistic in scope and application, but and therapeutic decisions (Maupome & Sheiham recently there have been suggestions of applying 2000). There is tion that the fast and efficient retrieval and proces- now an awareness of the significance of language, sing of clinical information is related to the symbols and semantics within the context of clin- structure of knowledge in a person’s memory. This ical situations where uncertainty is a dominant is particularly evident among expert clinicians feature (Sadegh-Zadeh 2001). The relatively sim- such as dermatologists and radiologists, who use ple computation of numbers in Bayesian theory visual cues from previous clinical experiences is being replaced by symbolic computations (Elstein & Schwartz 2000). Students, in contrast, designed to address uncertainty, and by appli- store their knowledge in a more disorganized and cations of heuristics or trial-and-error and the disjointed pattern, and retrieve it in a process of structure of knowledge and perception (Zadeh trial and error to locate and connect isolated bits 2001). However, we are not aware of a practical of information (Hendricson & Cohen 2001). From Clinical reasoning in dentistry 261 the perspective of cognitive psychology, it seems One interpretation of these findings is that that experienced clinicians function unconsciously during the process of clinical reasoning, regardless within the context of an ‘illness script’ that offers of the level of expertise, clinicians use illness various cues or action ‘triggers’ based on previous scripts, recognize patterns of conditions, and apply experiences with similar patterns (Charlin et al hypothetico-deductive reasoning in a forward or 2000). From this viewpoint, caries, for example, is backward direction between hypotheses and data. Recent reviews of clinical reasoning in the disease is present or absent (Bader & Shugars medicine endorse combining models of clinical 1997). Medical models of clinical reasoning have focused Balto & Al-Madi 2004, Knutsson et al 2001). Appar- mostly on the diagnostic process, which reflects an ently, the outcomes and processes of reasoning by underlying assumption that treatment-planning dentists are not very consistent. Comparing the automatically follows a ‘correct’ diagnosis (Elstein reasoning processes of dentists with different & Schwartz 2000). In acute settings with simple levels of expertise showed that experts used ‘for- problems this may be true. However, dental pro- ward reasoning’ to identify relevant information, blems range from acute to chronic conditions, such search for key information and organize the find- as acute toothache and chronic tooth loss, that usu- ings to form a diagnostic hypothesis. Students ally have a significant impact on quality of life and less experienced dentists generated an initial (MacEntee et al 1997). Management of chronic dis- hypothesis and then moved backward to confirm ease requires a sophisticated understanding of the or reject it. However, at all levels of expertise, some experience of disease and of related psychosocial clinicians moved back and forth between their issues that complicate the problems. For example, original and revised hypotheses to come up with the general health and psychosocial circumstances a final diagnosis. It seems that expert clinicians rely of elderly patients demand clinical decisions based heavily on their clinical experience to explain the on issues that extend beyond the confines of the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the biomedical model of disease (Ettinger et al 1990, disease, whereas students and inexperienced den- MacEntee et al 1987). Dentists who provide care tists rely more on textbooks and other information to frail elders have reported on ethical dilemmas acquired from didactic courses. Crespo et al (2004) such as obtaining consent for treatment when found the major difference between experts and patients are cognitively impaired or when there is novices to be the emphasis placed by experts on a conflict between a patient’s autonomy and the the impact of psychosocial issues such as the beha- dentists’ ethical principles (Bryant et al 1995), and viours and beliefs of patients. Expert dentists seem when care is rendered in the midst of conflicting to rely more on previous experience to construct an priorities (MacEntee et al 1999). Cost of dental care individualized treatment plan to address patients’ is usually an important factor when selecting treat- special problems and needs, rather than working ment options (Ettinger et al 1990). Financial issues through a hypothetico-deductive process to an can create a dilemma for dentists when there is a ideal treatment plan (Ettinger et al 1990). Clinicians interact with all such pro- blems, in context, to construct a ‘problem space’. With their recent hypothetical a range of clinical problems and improve their model of decision-making pertaining to diagnosis reasoning skills by ‘deliberate practice’ of framing and management of caries and periodontal dis- and solving problems and reflection on reasoning ease, White & Maupome (2003) made a good effort process (Eva 2005, Guest et al 2001, Norman 2005). Included in the decision-making historical relationship between the two profes- process are three pieces of evidence: (1) the sions. Medical decision theory has dominated patient’s needs and preferences; (2) individual much of the discourse, and has influenced such clinical expertise; and (3) external clinical evidence projects as computerized decision support sys- based on ‘systematic reviews of the scientific liter- tems. All are incorporated to achieve the optimal approaches that are strongly influenced by cog- oral health outcome within the biological, clinical, nitive psychology, such as the hypothetico-deduct- psychosocial and economic contexts. Closely To research such complex settings we need bet- related to this is the research into differences ter models of rationality, other than the Cartesian characterizing experts and novices, such as those reductionism typical of so much research in the lit- relating to forward and backward reasoning. Montgomery (2006) has recommended the recently, there is a growing realization that inter- adoption of a new understanding of rationality disciplinary approaches that synthesize insights based on Aristotle’s notion of phronesis, or practical from the different research traditions offer exciting rationality, arguing that this provides a more real- new ways of developing our understanding of clin- istic conceptual model for understanding clinical ical reasoning in dentistry. It can be argued that the approaches of the social sciences, in particular, same applies to dentistry. Research based upon offer the means both to explore clinical reasoning such ideas requires interpretive approaches. John Science and Medicine 48:407–420 Wiley & Sons, Chichester Akcam M O, Takada K 2002 Fuzzy modeling for selecting Bryant S R, MacEntee M I, Browne A 1995 Ethical issues headgear types. European Journal of Orthodontics encountered by dentists in the care of institutionalized 24:99–106 elders. Special Care in Dentistry 15:79–82 Bader J D, Shugars D A 1997 What do we know about how Charlin B, Tardiff J, Boshuizen H P A 2000 Scripts and dentists make caries-related treatment decisions? Academic Balto H A, Al-Madi E M 2004 A comparison of retreatment Medicine 75:182–190 decisions among dental practitioners and endodontists. Charon R 2006 Narrative medicine: honoring the stories of Journal of Dental Education 68:872–879 illness. Oxford Unversity Press, Oxford Clinical reasoning in dentistry 263 Crespo K E, Torres J E, Recio M E 2004 Reasoning process Hendricson W D, Cohen P A 2001 Oral healthcare in the 21st characteristics in the diagnostic skills of beginner, century: implications for dental and medical education. Journal of Dental Academic Medicine 76:1181–1206 Education 68:1235–1244 Higgs J, Jones M 2000 Clinical reasoning in the health Davis A G, George J 1988 States of health: health and illness professions. Butterworth- Dharamsi S 2003 Discursive constructions of social Heinemann, Oxford, p 3–14 responsibility.

The system is responsible for the circulation of blood through the tissues of the body buy generic shallaki line spasms from alcohol. Arising from the heart it divides discount shallaki 60 caps without prescription kidney spasms no pain, like the branches of a tree purchase shallaki 60 caps with visa muscle relaxant alcoholism, into smaller and smaller branches. In some organs, these vessels are somewhat different in structure from capillaries and are called sinusoids. Blood from capillaries or sinusoids is collected by another set of vessels that carry it back to the heart. Smaller veins join together (like tributaries of a river) to form larger and larger veins. Ultimately, the blood reaches two large veins, the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava, which pour it back into the heart. A special set of arteries and veins circulate this blood through the lungs where it is again oxygenated. This circulation through the lungs, for the purpose of oxygenation of blood, is called the pulmonary circulation, to distinguish it from the main or systemic circulation. The heart is a muscular pump designed to ensure the circulation of blood through the tissues of the body (20. Both structurally and functionally, it consists of two halves namely right and left. The ‘right heart’ circulates blood only through the lungs for the purpose of oxygenation (i. Each half of the heart consists of an infow chamber called the atrium, and of an outfow chamber called the ventricle. The right atrium opens into the right ventricle through the right atrioventricular orifice. The left atrium opens into the left ventricle through the left atrioventricular orifice. These valves allow fow of blood from atrium to ventricle, but not in the reverse direction. The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from tissues of the entire body through the superior and inferior venae cavae. It leaves the right ventricle through a large outfow vessel called the pulmonary trunk. This trunk divides into right and left pulmonary arteries that carry blood to the lungs. Blood oxygenated in the lungs is brought back to the heart by four pulmonary veins (two right and two left) that end in the left atrium. It is returned to the heart (right atrium) through the venae cavae, thus completing the circuit. It is made up (from right to left) by the right atrium, the right ventricle and the left ventricle. Note that the contribution of the right ventricle to this surface is much greater than that of the left ventricle. The two ventricles are separated by the anterior interventricular groove (‘b’ in 20. The right atrium and ventricle are separated by the anterior part of the atrioventricular groove (‘a’ in 20. Note the origins to show the left atrium which is hidden behind relationship of the sternocostal and diaphragmatic them. The outline of the root of the aorta is shown in dots surfaces to each other 404 Part 3 ¦ Thorax d. The sternocostal surface is bounded below by a sharp inferior border that separates it from the diaphragmatic surface. The region where the inferior border meets the left margin of the heart is called the apex. In the intact heart, this border is obscured from view by the parts of the aorta and the pulmonary trunk that lie in front of it. A small appendage arises from the upper and anterior part of the right atrium and overlaps the right side of the lower part of the aorta. A similar appendage arising from the left atrium (auricle of the left atrium) (20. The inferior or diaphragmatic surface is seen when the heart is viewed from below: a. It is formed in greater part (two-thirds) by the left ventricle, and to a lesser degree (one-third) by the right ventricle. The two ventricles are separated from each other by the posterior interventricular groove. They are separated from the corresponding atria by the posterior part of the atrioventricular groove. The atrioventricular or coronary sulcus, mentioned earlier, separates the atria from the ventricles. It runs downwards and to the right between the right atrium and the right ventricle. The part of the sulcus separating the anterior aspects of the left ventricle and atrium (‘b’ in 20. The posterior (or inferior) part of the sulcus lies at the junction of the diaphragmatic surface of the right ventricle with the right atrium (‘c’ in 20. The interventricular grooves mark the position of attachment of the ventricular septum to the outer wall of the heart. The drawing is made as if the walls and septa of the heart were transparent Chapter 20 ¦ the Heart and Pericardium 405 a. From here both grooves pass upwards, backwards and to the right and end by meeting the coronary sulcus. Note that how the anterior and posterior parts of the coronary sulcus become continuous with each other by curving around the margins of the heart. The opening of the superior vena cava is situated in its upper and posterior part, and that of the inferior vena cava into its lower part, close to the interatrial septum. The opening of the inferior vena cava is bounded by a semilunar fold of endocardium called the valve of the inferior vena cava. This opening is present just to the left of the opening of the inferior vena cava. In addition to these three major openings, there are numerous small apertures in the wall of the atrium for small veins called the venae cordis minimae. The sinus venarum and the atrium proper meet along a line that runs more or less vertically on the lateral wall of the atrium. This line is marked, on the internal surface of the atrial wall, by a muscular ridge called the crista terminalis. It starts on the interatrial septum, passes anterior to the opening of the superior vena cava and runs along the lateral wall of the atrium to reach the opening of the inferior vena cava, where it becomes continuous with the valve of that opening.

Gustavsson B 2004 Revisiting the philosophical roots of Sage Publications discount 60caps shallaki overnight delivery skeletal muscle relaxant quizlet, London buy discount shallaki line muscle relaxant anticholinergic, p 607–631 practical knowledge buy cheap shallaki 60caps on-line muscle relaxants quizlet. In: Higgs J, Richardson B, Abrandt Moore T W 1982 Philosophy of education: an introduction. DahlgrenM(eds)Developingpracticeknowledgeforhealth Routledge and Kegan Paul, London professionals. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, p 35–50 Parry A 1997 New paradigms for old: musings on the shape Habermas J (trans. Heinemann, London Polanyi M 1958 Personal knowledge: towards a post-critical Herbert R D, Sherrington C, Maher C et al 2001 Evidence- philosophy. Physiotherapy Reason P, Heron J 1986 Research with people: the paradigm Theory and Practice 17:201–211 of cooperative experiential enquiry. Person-Centred Higgs J, Titchen A 1995 Propositional, professional and Review 1:457–476 personal knowledge in clinical reasoning. In: Higgs J, Ritchie J 1999 Using qualitative research to enhance Jones M (eds) Clinical reasoning in the health professions. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, p 126–146 Australian Journal of Physiotherapy 45:251–256 Knowledge, reasoning and evidence for practice 161 Rycroft-Malone J, Seers K, Titchen A et al 2004 What counts knowledge and expertise in the health professions. Journal of Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, p 35–41 Advanced Nursing 47(1):81–90 Titchen A, Higgs J 2001 Towards professional artistry and Ryle G 1949 the concept of mind. In: Higgs J, Titchen A (eds) Harmondsworth Professional practice in health, education and the creative Sackett D L, Straus S E, Richardson W S et al 2000 Evidence- arts. Titchen A, McGinley M 2003 Facilitating practitioner- Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh research throughcritical companionship. National League for Nursing, New Titchen A, Manley K 2006 Spiralling towards York transformational action research: philosophical and Schon D 1987 Educating the reflective practitioner: toward a? practical journeys. Educational Action Research: An new design for teaching and learning in the professions. International Journal 14(3):333–356 Jossey-Bass, San Francisco Wittgenstein L 1921/1963 Tractatus logico-philosphicus. Shepard K F 1987 Qualitative and quantitative research in Suhurkamp, Frankfurt clinical practice. Physical Therapy 67:1891–1894 World Health Organization 2001 International classification Titchen A, Ersser S J 2001 the nature of professional craft of functioning, disability and health. Practitioners need to be able to knowledge 164 critically appreciate knowledge, generate knowl- edge from practice and recognize the practice Employing, creating and modifying knowledge epistemology that underpins their practice. Language serves as a tool for thinking, Disseminating and peer reviewing 169 learning and making meaning (Vygotsky 1986, Ongoing development 170 Wittgenstein 1958) (see Chapter 31). Knowledge Conclusion 171 is constructed in the framework of sociopolitical, cultural and historical contexts. Practice knowl- edge evolves within a dynamic ‘history of ideas’ (see Berlin 1979, Lovejoy 1940) contained in the particular practice domain and within the history of how ideas born in that practice domain have shaped and been shaped by that practice (Higgs et al 2001). Each of these dimensions and contexts of knowl- edge has particular relevance to how we use knowledge in reasoning and generate knowledge from within reasoning. During professional sociali- zation, practitioners learn the ways of being, acting, thinking and communicating that characterize their profession. In this chapter we extend this argument ing aware of, understanding and valuing it. Critical to the understanding and adoption of a position appreciation is a process of examining and seek- relating to practice epistemology. To say that ‘this ing to understand an activity or an object by as is the epistemological position that underpins my many means and from as many points of view practice’ is to recognize that my practice is carried as possible. This incorporates: out within the context of a certain discursive tra- reflecting upon its creator’s or originator’s dition (a scientific and professional community intentions, methods and values in this case) of knowledge generation. This tradi- recognizing the traditions and context within tion, with its rules and norms of practice, deter- which it was created mines what constitutes knowledge and what evaluating its achievements and failures strategies of knowledge generation are valid. In humanistic, psychosocial practice mod- Critical appreciation and professional judge- els, located in the human and social sciences and ment have much in common. Professional judge- the arts, knowledge is seen as being interpretive, ment can focus on the product of clinical theoretical, and constructed in social worlds reasoning, that is, the decisions or judgements that recognize and seek to interpret multiple made in clinical practice; this is comparable to the constructed realities. In emancipatory practice evaluation made by connoisseurs (Eisner 1985) models, located in the critical social sciences, who use critical appreciation to make judgements knowledge is recognized as being historically about their field of expertise (e. The pro- and culturally constructed, and historical reality cesses of clinical reasoning and critical apprecia- is something that, once understood more deeply, tion both involve using discretionary judgement can be changed in order to seek positive changes and self-evaluation (Freidson 1994, 2001). They are expected to seek out the best and practice are inseparable (see Fish & Coles and most salient knowledge available to deal 1998, Higgs et al 2001, Ryle 1949). Indeed profes- with practice tasks and problems and to recognize sional practice, with clinical reasoning at its core, when their knowledge is deficient, redundant could be viewed as knowing in practice. In such cases they need to pursue fessional knowledge should be considered not as further learning, reflect on practice to generate a repository of knowledge of the discipline com- experience-based knowledge, and seek out other bined with the individual practitioner’s store of people’s knowledge (including that of their clients) knowledge, but rather as a practice of knowing as input to professional decision making. Part of appreciating practice knowledge is recog- Thus the knowing and the doing of practice are nizing that what counts as knowledge is a matter of concurrent, intertwined journeys of being and perspective. Western society and in the health professions is Knowledge generation and clinical reasoning in practice 165 the largely unquestioned view of knowledge this process of acquiring knowledge as ‘internali- from the physical sciences or empirico-analytical zation of activity’, and Rogoff (1995) used the term paradigm. Thisisthe‘hypothetico-deductive’ ‘participatory appropriation’ to emphasize the approach, in which knowledge generation is dynamic, relational and mutual nature of learning. This process of appreciation requires us to sentationalism, the notion that theories (and lan- question previous values and entails a new the- guage) represent nature rather than the notion matic understanding of previously implicit ways developed here, that theories are created in the of seeing and understanding. In critique of this posi- cess, where individuals are placed in the position tivist epistemology (the idea that scientific propo- of critics who do not blindly accept what their pro- sitions are given to the senses by nature itself), fessional leaders or experts espouse, but actively the British philosopher Karl Popper (1959, 1970) question and interpret it in light of their own previ- argued that the discovery of scientific fact begins ous and current experience. They may in fact reject by a process of theoretical conjecture, not, as the the new or emerging knowledge and suggest alter- positivists would argue, through objective or natives. From this conjunction only can the circumstances that surround knowl- arise testable or ‘falsifiable’ hypotheses. Thus in edge use, creation and acknowledgement change, epistemological terms, science follows a process but the knower’s frame of reference (including or method involving disproof, not proof. One knowledge needs, values and knowledge abilities) cannot speak about truth in the traditional might also change. All these changes impact on sense, that a hypothesis matches reality precisely professional practice and must be internalized by or perfectly, but rather that empirical research both new learners and skilled practitioners. Theo- of this change may well occur around us, even ries that have withstood the strictures of empirical in some instances without our initial explicit testing or experimentation give scientists a degree awareness, but it can also arise from continuous of certainty and confidence about them. Employ- (individuals or groups) who are striving to know ing existing or learned knowledge in practice is about nature and experience. This view of knowl- not simply a matter of transferring this knowledge edge involves an appreciation of knowledge as to a new setting. This process customarily requires a sociohistorical political construct and recogni- modification, particularly because knowledge tion of the value of different forms of knowledge generated through research or by theorists is inev- for different communities and contexts. We are itably generalized, and does not always meet socialized (in life, education and work) to value the needs of the particular practice in the field. In practice, nally by them, an internalization that occurs when not only are propositional and non-propositional the evidence is seen to have relevance for their knowledge modified for and through practice, practice. In practical settings, professionals are but they are also combined, extended, converted continually adapting both formal public knowl- from one form to another and, most importantly, edge and their own informal knowledge to particu- particularized (see Fish & de Cossart 2007, Mont- lar cases, or they are extending existing knowledge gomery 2006).